Incompleteness, Computability, and Philosophy

Introduction

In the 20th century there was a push to axiomitize math, as people searched for a set of axioms from which all of math could be derived. In this search, they considered Peano Arithmetic (PA), a set of 6 axioms plus induction. However, in 1931 Godel released two incompleteness theorems that PA could not axiomitize all of math. His first incompleteness theorem shows the existence of statements that are not provable in PA, which were of the form “I am not provable”. His second incompleteness theorem shows that PA cannot prove its own consistency: in particular, the statement “PA is consistent”.

These results are interesting both technically and philosophicallly. From a technical perspective, the results have fascinating connections with computability theory. Philosophically, people have argued over the interpretation of Godel’s theorems since their inception. A typical, but contentious interpretation is that Incompleteness shows that the brain is more capable than a computer (in particular, a Turing Machine). Besides cognition and AI, there are also discussions about the foundations of math and epistemology (how do we know things).

I hope to cover both the technical and philosophical sides in this post. The technicals will be closely based on Stephen Cook and Toni Pitassi’s lecture notes, while the philosophical discussion will be based on the views of some prominent mathematicians. This post will be technical, but in the interest of concision and readability, I’ll write down only the key arguments and put the rest of the technical proofs in the appendix.

The First Incompleteness Result

Proof Sketch

A stronger version of Godel’s first incompleteness result is that the language, True Arithmetic (abbreviated TA), cannot be axiomitized. What is TA and why is it relevant? On a high level, TA contains all “True” statements formed using the vocabulary of Arithmetic. As we’ll see, the fact that TA can’t be axiomized is a statement about how complex it is: how we cannot easily capture what statements are (or are not) in TA using a certain types of formulae. At its heart, the first incompleteness result makes a claim about TA’s complexity.

We’ll see that this formulation of Godel’s first incompleteness result also implies other, more familiar consequences. In particular, for any set of axioms (e.g. those constituting PA), there is always some statement in TA that can’t be proved from them. Before diving in, we’ll first clarify our notation.

Notation:

-

By arithmetic, we mean the set of sentences formed from the vocabulary \(L_A = [0, s, +, \cdot; =]\).

-

Also, let \(\mathbb{N}\) be the standard model for \(L_A\): which assigns each symbol their usual interpretation: E.g. \(\cdot\) means multiply, the symbol 0 means the value 0, the symbol s0 means 1, and the symbol sx means x + 1. So s is a “successor” function.

-

Let \(\phi_0\) denote the set of all \(L_A\) sentences (either true or false).

-

Let \(TA\) (True Arithmetic) be the set of sentences with vocabulary \(L_A\) that are true under the standard model, \(\mathbb{N}\). That is, \(TA = \{ A \in \phi_0 : \mathbb{N} \models A\}\), where we use \(\models\) to denote “logical consequence”. In particular, \(\mathbb{N} \models A\) means that \(A\) is a logical consequence of \(\mathbb{N}\).

We’ll also review some concepts from computability theory:

-

relation/language - a relation (equivalently, a language) is a subset of all bit-strings. E.g. Prime(x) is a relation that contains all strings of bits that encode prime numbers

-

r.e./recognizable - a language is r.e. (equivalently, recognizable) if a Turing Machine (TM) recognizes it. i.e. there’s a TM that accepts all elements in the language.

-

recursive/computable/decidable - a language is recursive (equivalently, computable or decidable) if a Turing machine decides it. i.e. there’s a TM that when given an element in the language, it accepts; when given an element not in the language, it rejects.

Now we are ready to introduce new concepts.

Definition: We say that arithmetic formula A represents relation R if whenever a string x is in R, A(x) is a true statement in arithmetic. Conversely, when x is not in R, A(x) is a false statement.

For instance, the relation “x divides y”, containing all x and y where x divides y, is represented by the following arithmetic formula. One can see that when x dividies y, the corresponding statement is true, and false otherwise.

\[A(x, y) = \exists z (x \cdot z = y)\]With the concept of arithmetic formulas representing relations, we define an important term.

Definition: A relation R is arithmetical iff it is represented by some formula.

We now define some special types of arithmetic formulas that we will use in the proof sketch.

Definition: A \(\Delta_0\) formula is one where the quantified variables are bounded (in \(\forall x \leq 4\), x is bounded). Further, a relation R is a \(\Delta_0\) relation iff some \(\Delta_0\) formula A represents R.

As an example, the relation Prime(x) is represented by the following \(\Delta_0\) formula, which roughly says that “x is bigger than 1 (aka the successor of 0, s0), and for any y less than x that divides x, the remainder is either 1 or x”.

\[(s0 < x) \wedge \forall z \leq x, \forall y\leq x (x = z \cdot y \supset (z = 1 \vee z = x))\]Definition: An \(\exists\Delta_0\) formula is one of the form \(\exists y A\), where A is a \(\Delta_0\) formula. Further, a relation R is a \(\exists\Delta_0\) relation iff some \(\exists\Delta_0\) formula A represents R.

From these definitions, we claim the following.

Key Theorem: A relation is r.e. if and only if it is \(\exists\Delta_0\)

Every r.e. relation can be represented by an \(\exists\Delta_0\) arithmetic formula, and conversely every relation represented by an \(\exists\Delta_0\) formula is r.e. The proof we leave in the appendix. As we’ll see below, a version of Godel’s first incompleteness theorem follows from this key result.

Corollary: TA is not r.e.

Proof: Consider the famous Halting relation, \(K\).

\(K\) (Halting Problem): for a bit-string \(x\), \(x \in K\) if and only if \(x\) encodes a Turing Machine (TM) that halts when run on input string \(x\)

It is well known that \(K\) is r.e. Thus, \(K\) is represented by some \(\exists \Delta_0\) formula \(A(x)\). Crucially, this means that \(K^c\), the complement of the Halting problem, is represented by \(\neg A(x)\). Thus,

\[n \in K^c \iff \neg A(n) \in TA\]The crux of this reduction argument is that if TA is r.e., then \(K^c\) is also r.e. The final (well known) key fact is that \(K^c\) is actually not r.e. Thus, TA cannot be r.e. either. \(\blacksquare\)

This last corollary is a statement about the complexity of TA–how complicated the relation, TA, is. We’ll say more about later.

While it doesn’t look like it, this corollary implies Godel’s first incompleteness theorem. To see this, we’ll introduce a few more definitions.

Definition: A theory is a set \(\Sigma\) of sentences closed under logical consequence (\(\models\)). That is, if \(\Sigma \models A\), then \(A \in \Sigma\).

- \(\Sigma\) is consistent iff \(\Sigma \neq \phi_0\).

- \(\Sigma\) is complete iff \(\Sigma\) is consistent and for all sentences A, \(\Sigma \models A\) or \(\Sigma \models \neg A\) (but not both).

- \(\Sigma\) is sound iff \(\Sigma \subset TA\)

Roughly, a theory is sound if it does not have any false statements.

A theory is consistent if it doesn’t have both \(A\) and \(\neg A\). Note that if a theory \(\Sigma\) did have both a statement and its negation, then any statement in \(\phi_0\) would be a logical consequence of the theory, and thus \(\Sigma = \phi_0\). That is, if we claim that a statement A is both true and false, then anything follows after that. (Double-think: If Big Brother can convince you that something is simultaneously true and false, then they can convince you of anything). Note, however, that a theory may have “false” statements but still be consistent, if it doesn’t contain the corresponding negation.

Finally, a theory is complete if it is consistent and always proves either \(A\) or \(\neg A\)

Definition: If \(\Sigma\) is a theory and \(\Gamma \subset \Sigma\), then \(\Gamma\) is a set of axioms for \(\Sigma\) iff the following two conditions are met

- \(\Gamma\) is recursive

- \(\forall A \in \Sigma, \Gamma \models A\). That is, \(\Gamma\) derives (“summarizes”) all of \(\Sigma\)

It turns out the following key claim is true.

Theorem: A theory \(\Sigma\) is axiomitizable iff it is r.e.

We will omit a proof for this, but the immediate consequence of this theorem and the fact that TA is not r.e. is that TA is not axiomitizable. This is essentially the statement of Godel’s First Incompleteness Theorem. Any set of axioms is insufficient for proving all true statements in True Arithmetic. No matter which (sound) axioms we choose, there is always something in TA that’s outside what we can prove from those axioms. In particular, there is a statement in TA that’s not provable in PA.

Theorem (Godel): TA is not axiomitizable!

Although not axiomitizable, note that TA is complete, sound, and consistent. Thus,

Corollary: Any sound, axiomitizable theory is incomplete

Proof: If \(\Sigma\) is sound, then \(\Sigma \subset TA\), and if it is axiomitizable, then \(\Sigma \neq TA\). Thus, there is an \(A \in TA\) (that is true) such that \(A \notin \Sigma\). Furthermore, \(\neg A \notin \Sigma\) because \(\neg A\) is false and \(\Sigma\) is sound. Thus, \(\Sigma\) is incomplete. \(\blacksquare\)

Remark: Zermelo Fraenkel set theory with the axiom of choice (ZFC) is regarded as strong enough to formalize all “ordinary” mathematics. If we translated all statements in the language of arithmetic to statements in the language of set theory, there will still be sentences in TA whose translations into set theory are not theorems of ZFC.

Remark: Although unlikely, it’s possible that a number of famous conjectures may be true, but do not follow from ZFC.

- Goldbach’s conjecture: every even integer is the sum of 2 primes

- Riemann Hypothesis

- P \(\neq\) NP

The Arithmetic Hierarchy and Tarski’s Theorem

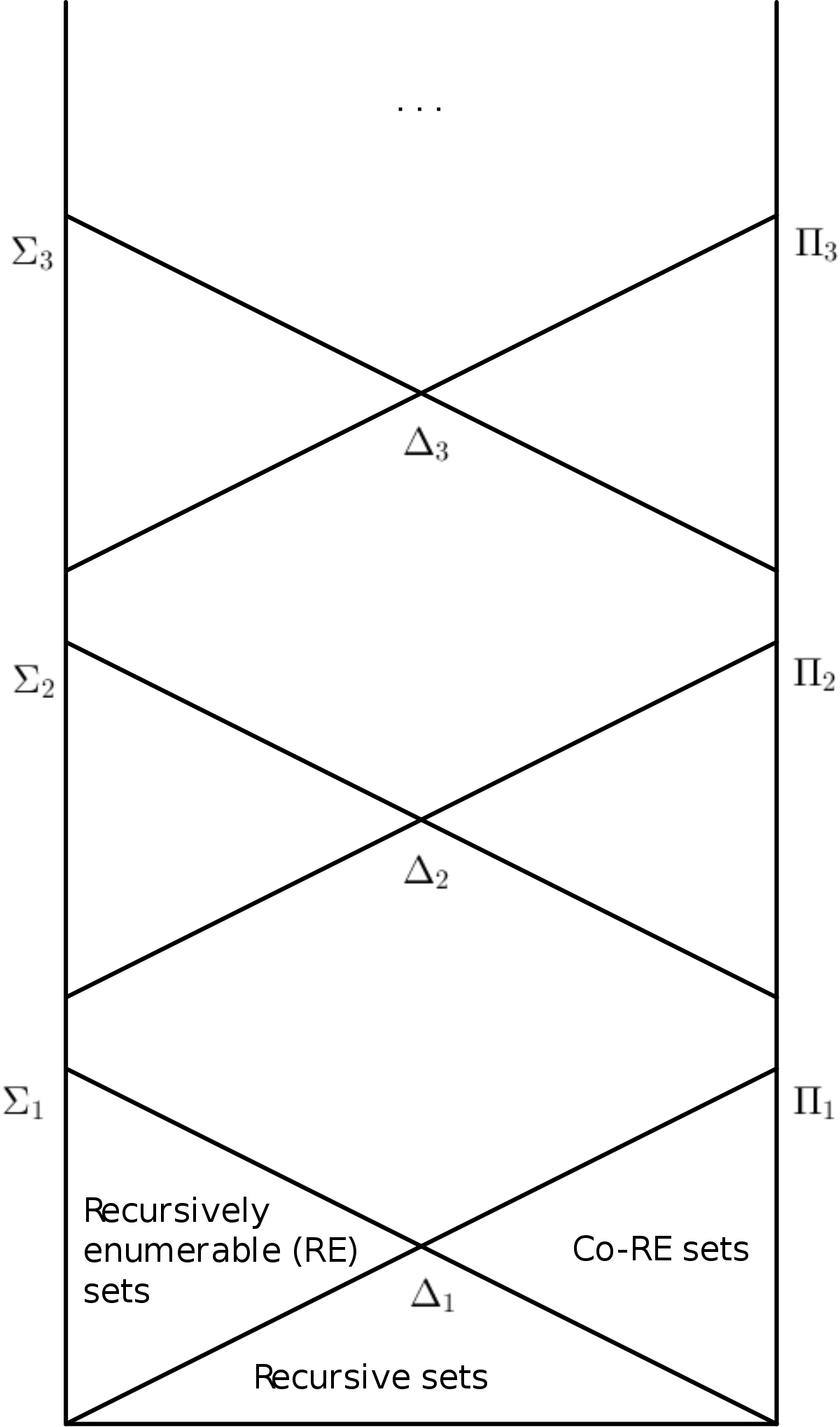

We showed above that TA is not r.e. In fact, we can prove a much stronger result: TA is not arithmetical. This is Tarski’s Theorem. This result is stronger in that it asserts the complexity of TA is much higher than simply “not r.e.”. To make reference to complexity clear, we will introduce the Arithmetic Hierarchy (AH), depicted below.

Each label, e.g. \(\Sigma_1\), corresponds to a set of relations. AH is a hierarchy of these sets of relations, ordered by complexity. Relations that belong to the “higher” sets are more complex in the following sense.

Each set depicted is characterized by arithmetic formulas of a particular form. For instance, \(\Sigma_1\), on the bottom left, is characterized by \(\exists \Delta_0\) formulas. As we proved earlier, this set consists of all r.e. relations, because a relation is r.e. iff it is representable by an \(\exists \Delta_0\) formula. The set \(\Pi_1\), bottom right, consists of co-r.e. sets, which are represented by the negation of a \(\Sigma_1\) formula. For \(k \geq 1\), we define a \(\Sigma_k\) formula to be of the form:

\[\exists y_1 \forall y_2 \exists y_3 ... Qy_k A(x, y_1, ... y_k)\]Where the quantifiers alternate between exists and for-all. Note that for \(k \geq 2\), \(\Sigma_k\) relations are far more non-computable than the Halting problem (No TM can even hope to recognize such a language).

Tarski’s theorem says: not only is TA not r.e., it is not even arithmetical. TA isn’t co-r.e., \(\Sigma_2\), \(\Sigma_3,... etc.\), or anything in AH; it is wildly difficult to compute!

Theorem (Tarski): TA is not arithmetical.

Proof: The proof uses self-referential sentences. Consider the sentence F: “I am false”. If F is true, then this means that F is false, which seems like a contradiction. By itself, this isn’t (formally) a contradiction.

But now suppose, towards contradiction, that TA is arithmetical. This means that there exists an arithmetical formula, A, that when given a statement in arithmetic, tells you whether that statement is true (i.e. in TA). This is a strong assumption since it implies that whether an arithmetic statement is true can be succinctly captured in an arithmetic formula.

Then, we reach a contradiction if we ask what A outputs on F. If A outputs “true” on F, then F must be false–If A outputs “false” on F, F must be true!

\[A(F) = 1 \iff F \text{ is false} \iff A(F) = 0\]We conclude that such an arithmetic formula, A, cannot exist. That is, TA is not arithmetical. Roughly, we conclude that TA is such an exceedingly complicated relation that it cannot be captured by any particular arithmetic formula in the way that, say, Prime(x) can.

The actual proof in reference [1] essentially formalizes what we sketched here. \(\blacksquare\)

Finally, note that all r.e. relations are arithmetical, as \(\Sigma_1 \subset AH\) (But not all arithmetical relations are r.e.). Thus, Tarski’s theorem immediately implies the result we showed earlier: TA is not r.e.

Undecidability Results

There are a variety of interesting connections between Incompleteness and Undecidability that we are now in a position to discuss. Roughly speaking, the difference between undecidability/decidability corresponds to complexity–is a relation decidable (recursive) or undecidable (harder than recursive). There are results for the complexity of a theory in terms of whether they’re sound, complete, etc.

First, we define the theory, VALID: the set of statements that are true under any interpretation of \(L_A\) (under any “model”).

Definition: VALID = \(\{ A \in \phi_0 : \quad \models A\}\)

VALID is also the smallest possible theory. For any theory \(\Sigma\), \(VALID \subset \Sigma\). It turns out VALID is also undecidable, but we won’t show the proof.

Theorem (Church): VALID is undecidable.

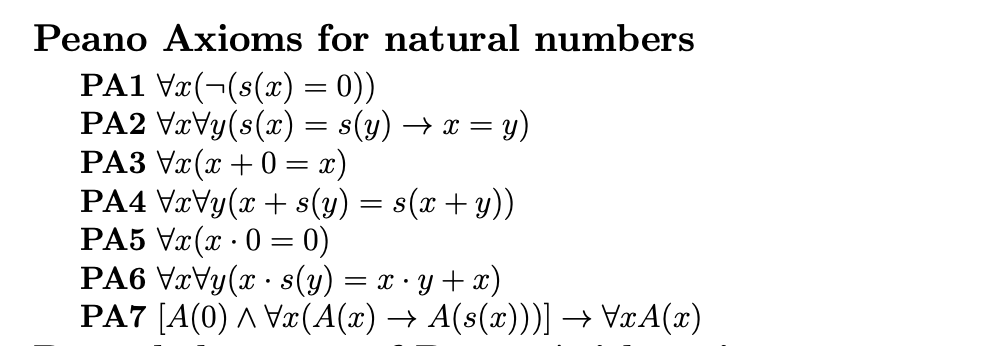

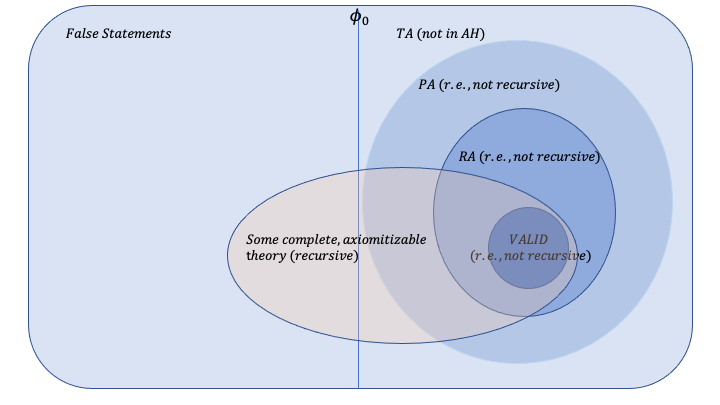

We also bring up results related to PA and RA. The axioms of PA are depicted below (note that \(s(\cdot)\) is the successor function, so \(s(x)\) means x + 1), while those of RA includes the first 6 axioms of PA, but not the seventh, inductive axiom. In its place, RA has 3 extra axioms that we won’t show here.

Finally, we state some results about these theories without proof. Recall from before that sound, axiomitizable theories are incomplete. Along similar lines,

Theorem: Every sound extension of RA (including PA) is undecidable.

An extension of RA is simply a theory that contains RA. So interestingly, any (axiomitizable) theory \(\Sigma\) such that \(RA \subset \Sigma \subset TA\) is both undecidable and incomplete.

So far, we’ve discussed undecidable theories. Which theories are decidable?

Theorem (Decidability Theorem): Every complete, axiomitizable theory is decidable.

From a previous result, it also follows that every axiomitizable, complete theory is not sound. Thus, axiomitizable theories that are complete are not only decidable, they are necessarily unsound (containing untrue theorems).

Final Remarks

To sum up, Godel’s first incompleteness theorem can be thought of as a statement about the complexity of TA (and the inability of a sound, axiomitizable theory to encompass all of TA). Using Godel’s theorem along with these undecidability results, we depict a visual landscape below that shows VALID, RA and PA, and TA. In this landscape, each theory has two defining parameters: the space it takes up (what statements/theorems it contains) and its complexity.

Remark 1: Confusingly, Godel also proved “Godel’s completeness theorem”. However, “completeness” in that theorem is used a different context and harbors a different meaning. Completeness in his completeness theorems refers to completeness of the LK proof-system: every sentence in VALID has an LK proof. In contrast, for a theory to be completeness in the sense of his incompleteness theorems, it has to contain every true sentence in TA (If \(\Sigma\) has axioms \(\Gamma,\) then it is complete if every statement in TA has an LK-\(\Gamma\) proof). TA is strictly larger than VALID beause VALID are sentences that are true under any model, while TA are sentences that are true under the standard arithmetic model (\(\mathbb{N}\)). Thus, these two theorems are talking about completeness with fundementally different meanings, and do not contradict.

Remark 2: The incompleteness and undecidability results arise from the complexity of \(L_A\). This complexity is derived from there being a \(+\) and a \(\cdot\) in the vocabulary. Indeed, if we consider the same vocabulary but without \(\cdot\), we get Presburger Arithmetic, which is decidable and has an axiomitization. The complexity of true sentences is much lower if the vocabulary has only \(+\). Euclidean Geometry is also a relatively simple theory and is decidable, if I remember correctly. Thus, TA transcends both these theories in complexity.

The Second Incompleteness Result

In its original form, Godel’s first incompleteness theorem showed the existence of statements with no proof in PA. In the previous section, we discussed a more general result that pertained to any sound, axiomitizable theory (not just PA).

However, let’s reduce our scope a little and look at Godel’s original construction, which has the same flavor as Tarski’s. Consider the following sentence, G, encoded in arithmetic, which says

G: “I have no proof in PA.”

Note that G is true, since if it were false, it would have a proof, violating soundness of PA. Since G is true, this means G has no proof in PA.

Theorem (Godel's First Incompleteness Theorem, Original form): If PA is consistent, then PA does not prove G.

With these strange self-referential statements underpinning Godel’s first theorem, one wonders whether there are actually any meaningful theorems that may not have a proof in PA or ZFC. Godel’s second theorem offers a more satisfying “unprovable” theorem.

Theorem (Godel's Second Incompleteness Theorem): If PA is consistent, then PA cannot prove its own consistency.

Refer to [1] for the proof, but roughly, one can show that PA proves the statement “If PA were consistent, then G is true”. Thus, if PA is consistent, then PA cannot prove its own consistency, or else it would also prove G (contradicting the first incompleteness theorem).

Remark: Note that since G is “I am not provable in PA”, then the statement “If PA were consistent, then G is true” is equivalent to “If PA were consistent, then G is not provable in PA.” This is exactly the statement of the first incompleteness theorem. Thus, the crux of the proof for the second incompleteness theorem is to show that the first incompleteness theorem can be formalized in PA.

Philosophy

We’ll now get into higher level, philosophical interpretations of Godel’s theorems. I haven’t read these in too much depth, so I’ll just outline most basic arguments, drawing ideas from Roger Penrose, Scott Aaronson, and Alan Turing. I’ll also add in my own thoughts and questions.

Foundations of Math

The most direct philosophical implication of Incompleteness is that it poses serious obstacles to those who are trying to completely axiomitize mathematics (“Hilbert’s Program”). Suppose we all agree on some sufficiently complex vocabulary \((L_A)\) and some interpretation for the symbols in that vocabulary (e.g. the standard interpretation, \(\mathbb{N}\)). Then we can’t summarize all true statements with a simple (recursive) set of axioms.

There’s debate on whether Incompleteness has concrete implications for different philosophies of mathematics, such as Logicism and Intuitionism. We’ll briefly define Logicism

Logicism: All the objects forming the subject matter of those branches of math are logical objects; Further, Logic is capable of generating a mathematician’s ‘first principles’: the basic definitions of a branch of math. Every process in mathematics is a logical process. [3]

Logicism makes very strong claims about the power of Logic, with a flavor that’s reminiscent of Plato. Plato claimed that there were abstract “Forms” from which all truths were derived. The “Forms” served as first principles to justice, from whcih everything that was just could be derived. He viewed the ability to acquire these first principles and to deduce truth from them as the ultimate cognitive capability (and that philosophers, the only people with this capability, ought to be king).

Logic within a formal proof system, at least, seems to fall short of this Platonic ideal. There isn’t a set of “forms” or axioms for all of TA, much less all truths for justice and human behavior. Incompleteness seems like a strong barrier to Logicism. Apparently, Godel also argued against logicism using Incompleteness [2].

Limits of AI?

The argument against Logicism in the previous section cited the limitation of formal logic. This begs the question: can a human’s reasoning capabilities be described as a formal proof system? Are we nothing more than theorem provers working within the confines of some proof system? Or if not, does Incompleteness say anything definitive about human cognition being more powerful than a computer? The latter is a loaded question, with high caliber mathematicians arguing either side.

Regarding the anti-mechanism argument in favor of super-Turing human cognition, Philosopher J.R. Lucas claimed that Incompleteness is evidence for super-Turing cognition since

Given any machine which is consistent and capable of doing simple arithmetic, there is a formula it is incapable of producing as being true … but which we can see to be true.

This refers to the first of Godel’s theorems–Any given formal system F (like PA) can’t prove the sentence G(F): “I cannot be proved in F”, yet this is something we as humans can “see” as true via some “meta” reasoning. If we think of all machines as being constrained to some formal proof system, then the conclusion is that we are far smarter than any machine. What do you think of this argument?

This is the view of Nobel Laureate Roger Penrose. Penrose, in fact, believes in a much stronger statement: the brain is not just super-Turing, it uses so-far undiscovered laws of quantum-gravity to do information processing that classical computers can’t. Furthermore, all this super-Turing computation happens on a micro-level in the microtubules of our cells. This is his central claim in his famous book, The Emperor’s New Mind [4].

However, the Incompleteness-based anti-mechanism argument is arguably problematic. The standard rebuttal is that the anti-mechanistic argument mistakenly cites the first Incompleteness theorem as saying “G(F) has no proof in F”. In fact, the first Incompleteness theorem says that “If F is consistent, G(F) has no proof in F”. Thus, if a human really can “see” the truth of G(F), finding a proof that a machine couldn’t, then surely the human must also be able to “see” that F is consistent.

Let’s try test this supposition. Here are the axioms to Peano Arithmetic, PA. Can you “see” that these form a consistent theory–that there will be no theorem along the way that is proved both true and false by PA?

Moreover, even assuming someone “saw” PA’s consistency, how would you even verify that they could? As such, the typical exchange between the anti-mechanist and the skeptic goes as following, where F is some formal proof system like PA.

Skeptic: “When you say you saw the truth of G(F), how can I know that you’re doing something a machine can’t”

The anti-mechanist replies: “This is where Godel comes in–the machine is constrained to a formal system while we are not. Thus, it cannot prove G(F)”

The skeptic coolly asks: “How do you know you aren’t also constrained to a formal system”

The anti-mechanist retorts: “Because I can see F’s consistency”

The skeptic replies: “Really? how can you know you’re not just, say, assuming its consistency?”

The anti-mechanist, indignant, exclaims: “Because I can feel that F is consistent. The machine, on the other hand, is just shuffling symbols around”.

To which the age-old rebuttal applies: “How do you know the machine didn’t feel that F is consistent, too?”

In this way, the Incompleteness-based anti-mechanism argument is just the same age-old anti-mechanism argument that machines can’t “feel” as we humans do. Ultimately, it is unsatisfying because there’s no way to tell if someone actually ascertains the consistency of F, or if they are just assuming its consistency a priori. If the latter is the case, then if we gave a machine the same freedom to assume consistency of F, it would also be able to prove G(F). And then the alleged gap between human and machine’s capabilities would disappear. In short, it’s unclear that we can take the following for granted:

(1) Humans can “see” truths machines can’t

(2) Machines are necessarily confined to a formal system

Alan Turing and Scott Aaronson both subscribe to this view. On the other hand, Godel subscribed to a version of the anti-mechanist view, though a more cautious version than the one above [2]. What do you think of it? Is the refutation above just pendantic, or is there actually substance to it?

Whichever side you believe, it’s at least not straightforward to use Incompleteness to claim that the human mind is super-Turing, or that AI is fundementally limited.

Epistemology

A question that lingers in my mind is: what is an accurate characterization of our cognitive abilities–in particular, our ability to reason? We’ve always had an intuitive ability to reason without needing the development of formal logic. We can talk about a “proof by contradiction” without the need for a notion of a “contrapositive”. We can talk about “definitions” and “induction” without the need for formal axioms. We (by we, I mean Godel) proved highly-nontrivial results about logical proof systems using our own deductive facilities.

What is it that lets us reason according to rules we never even formalized? Are we mechanistic proving machines, just working in a stronger formal proof system? Or do we truly possess some super-Turing ability to gaze into the Platonic heavens?

My second question is around our perception of true and false. Labeling things as true and false is the most intuitive way for us to make sense of the world. Yet, if you examine that closer, perhaps that will begin to seem arbitrary as well. Could we maybe reason in a way so as to assign statements a continuous value, instead of 0/1? Like a “degree of truth.” One reply I’ve received to this question is that although we can develop proof systems where statements take on values besides 0 and 1, it’s just simplest to have a true/false value assignment. And simplest is always best! I find this argument mostly believable, but part of me still wonders if perceiving things as true/false is fundementally arbitrary. Maybe it’s not arbitrary to you–what do you think?

Why Math Works

Quantitative theories have provided exceptionally accurate predictions about our world–Newtonian mechanics and gravity, quantum mechanics, relativity, groups, games, economics, probability, complexity, quantum computing, etc. As complex as the universe is, several truths about it can be described in terms of some simple axioms, like those used to generate these mathematical theories. That’s pretty amazing because it seems like it didn’t have to be this way. To what does the universe owe such a kindness? I feel it would have been conceivable too if, instead, the universe was just unintelligibly complex.

I suppose there is no answer to why the universe would be inherently simple–just that aspects of it are. There is order that we can describe and make sense of using simple axioms. After all, isn’t that the founding assumption of math?

What usually seems amazing is not the axioms themselves, as those often seem fairly self-evident. But the vast array of complex theorems you can derive from them. In PA, the first axiom “There is no number whose successor is 0” is not so amazing by itself, yet theorems you can derive, like Fermat’s last theorem, are truly remarkable. Newton’s laws are concise, but the array of physical scenarios you can analyze with them (all the Intro Physics exams ever written) seem far more remarkable. Yet, even though we tend to find the axioms’ deductions amazing, the axioms themselves do “summarize” all these truths, in a way. Thus, perhaps instead we ought to marvel at the axioms for their simplicity, not their consequences.

Of course, not all truths are derivable from axioms. TA is too complex to be captured entirely by an axiomitizable theory, as we saw with Godel’s first theorem. But all the same, axiomitizable theories do extremely well in describing our world, as theories like ZFC basically capture all mathematics we have so far. So perhaps some truths in the universe are not modeled by simple laws (in fact, maybe 99.99% of them aren’t). But even so, the 0.01% of them that are governed by simple laws allow for the highly accurate, elegant theories we have today. And even if the “simply-modelable” slice of truth is actually a miniscule fraction of all truths, they are clearly still exceedingly useful.

Final Remarks

To end this post, I wanted to point out how intricately connected CS is to Logic. In my opinion, Incompleteness is among the most elegant mathematical results, and it will take your thoughts to weird and interesting places, even beyond the math itself. To this point, Aaronson once jokingly said that CS ought to be renamed “Quantitative Epistemology,” a suggestion I find endearing.

References

[1] https://www.cs.columbia.edu/~toni/Courses/Logic2021/Notes/Incompleteness.pdf

[2] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/goedel-incompleteness/#Mat

[3] https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logicism/

[4] Quantum Computing since Democritus – https://www.scottaaronson.com/democritus/

Appendix

Key Theorem: A relation is r.e. iff it is \(\exists\Delta_0\)

Proof: This theorem follows from the following 3 claims.

Lemma: Every \(\Delta_0\) relation is recursive

Proof: Roughly, this says that a relation that has a corresponding \(\Delta_0\) formula, A, can be decided by some TM. Indeed, to check if an element x is in the relation, our TM would evaluate the (bounded) formula A on x. \(\blacksquare\)

Theorem: Every \(\exists\Delta_0\) relation is r.e.

Proof: An \(\exists\Delta_0\) relation R is of the form \(\exists y A\), where A is \(\Delta_0\) and represents a recursive relation S(x,y). Then, \(R(x) = \exists y S(x,y)\), which is r.e. by definition \(\blacksquare\)

Regarding the first lemma, note that the converse is not true: not every recursive relation is \(\Delta_0\). Regarding the second theorem, note that while every r.e. relation is arithmetical, not every arithmetical relation is r.e.

Moving forward, it turns out that the converse to the above theorem is also true. This culminates in the famous “Exists-Delta” theorem.

Theorem (Exists Delta): Every r.e. relation is \(\exists\Delta_0\)

See reference [1] for its elegant proof. The proof hinges on the fact that the “graph” of a recursive function is \(\exists\Delta_0\). To show this, you use the Chinese Remainder Theorem to encoding sequences of bits (in particular, the cells of the tape of a Turing Machine) into two integers.