Game Theory of Poker

Thanks to Collin and Bennett for editing this post

Introduction

This article aims to explain game theory principles in Poker and provide intuitive heuristics to apply in your game.

Poker is an imperfect information game as players don’t know each others’ hole cards. In many ways, this makes poker harder than perfect-information games (where players see the entire game state), such as Tic-tac-toe and chess, because of the ability to bluff.

Bluffing makes your strategic considerations dependent on your private information and your opponents’ strategies. Not only do your strategic considerations become probabilistic (due to a lack of information), they also become “K-level”. “What does my opponent think that I think that they have?” is the type of “K-level” thinking that bluffing induces. Thus, to describe what is optimal in poker, we need the following game theoretic concepts:

- expected value (EV)

- nash equilibrium (NE)

- best response (BR)

- exploitability

as well as some useful poker-specific concepts:

- ranges

- polarization

- balancing bluffs

We will illustrate these concepts by providing a principled analysis of a simplified poker game. TLDR, the 3 key takeaways are:

-

Playing a NE strategy is optimal in the sense that the best your opponent can do, EV-wise, is to also play a NE strategy. Although no one plays a perfect NE strategy, a NE strategy serves as a solid baseline strategy from which you can deviate if you see that your opponent has an exploitable tendency.

-

You and your opponent’s ranges determine what your NE strategy should be. Range Polarization and Equity are the two key range considerations when making decisions: do you have more nutted hands than your opponent, and are your hands stronger on average?

-

Betting has two purposes: getting value from your opponent and denying equity from your opponent’s hands. Regarding the latter, you should choose a sizing that makes a large part of their range indifferent to calling or folding. This “targeted” bet-sizing ensures that you maximize your own EV while putting your opponent in difficult spots, from which they will make mistakes.

Rules of NLH

This section provides the rules for the full No-limit Hold’em (NLH) game. This is not the simplified game we are analyzing, but the rules are included for the reader’s context.

NLH Rules – In two player No-Limit Hold’em, both players are dealt 2 cards, and there are up to 5 community cards in the middle. You make 5-card hands with your private cards and the community cards, and you win by either making the best 5-card hand or by making the opponent fold. There are 4 rounds of betting– preflop, flop, turn, and river. After the preflop round, 3 cards are dealt out (the flop), and the flop betting round commences. After this, the 4th card (the turn card) comes, followed by a betting round. Finally, the 5th card (the river card) is dealt, followed by one final round of betting.

Terminology

Position – you have position when you act after your opponent. This is an advantage because you can see what they do before making your decision.

IP – in position (acting last)

OOP – out of position (acting first)

Equity – A player’s equity is their chance of winning the hand by making the best hand by showdown (i.e. not by causing the opponent to fold)

EV – An action or strategy’s EV is how much money you make in expectation by playing it.

Nutted hands – hands whose strength is among the strongest possible (say, top 10%)

Value hands– “good” hands that are bet with the intention of being called by the opponent’s worse hands

Bluff hands– “bad” hands that are bet with the intention of folding out the opponent’s better hands

We now present a simplified poker game that we can analyze by hand.

A Simplified Poker Game

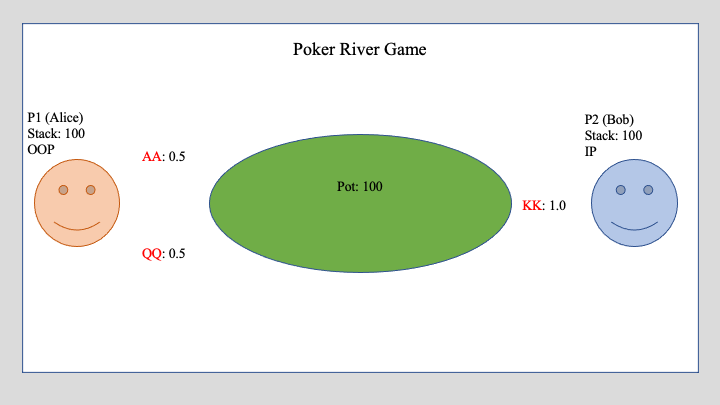

Definition 1.1 (Poker River Game): There are two players, P1 (Alice) and P2 (Bob). To start, there is 100 in the pot and both players have a stack of 100. P1 goes first, choosing either to check (x) or to bet (b) any amount. If P1 checks, P2 can check (x), or bet (b). If P1 bets, P2 can fold (f), call (c), or raise (r). Action alternates in this way, until one player either folds or calls. In the latter case, the players showdown their hands, and the better hand wins.

First, because a player doesn’t generally have enough information to pinpoint their opponent’s particular hand, we need the notion of a range to describe the possible hands their opponent could have, along with what probability they estimate their opponent to have it.

Definition 1.2 (Poker Range): A player’s range is a probability distribution over the cards they can have. Ranges, as perceived by an opponent, depend on the opponent’s current information set: their private cards, the public cards, and both players’ actions and position in the hand.

We will study the Poker River Game where, at the start of the game, P1 has range \(\{AA : 0.5, QQ : 0.5\}\) (i.e. AA or QQ with equal probability), while P2 has range \(\{KK : 1.0\}\). Let’s further assume that both players know each others ranges and strategies perfectly, so that they can instanteously adjust their own strategies in response to their opponent’s strategy. These are strong assumptions, but in the subsequent section, we will comment on the circumstances where these assumptions are reasonable.

Naive Suboptimal Strategy 1.3 (P1 always bets):

Suppose P1’s strategy was to bet 100% of her hands for an amount, \(100\). Against P1’s betting range, \(\{AA : 0.5, QQ : 0.5\}\), P2 wins 50% of the time, when against QQ (winning 100 pot + 100 bet), and loses the other 50% of the time, when against AA (losing $100). Against this strategy, P2 has a simple counter-strategy: to call with 100% of his hands–in fact, this is his best response. The expected value of P2’s counter-strategy is:

\[EV_2 = 0.5 (200) + 0.5 (-100) = $50\]Because this game is a zero-sum game, it must be that \(EV_1 + EV_2 = pot = 100\). Hence, \(EV_1 = 50\). However, P1 actually has a strategy with a better EV than 50. We claim the following:

Claim 1.4 (Nash Equilibrium for Poker River Game): P1’s nash equilibrium (NE) strategy is to bet 100% of her AA, bet 50% of her QQ, and check the other 50% of her QQ. P2’s NE strategy, when facing a bet, is to call 50% and fold 50%; and facing a check, P2 checks 100%. For this NE,

\(EV_1 = 75, EV_2 = 25\)

We’ll just discuss, intuitively, why this strategy is a NE. For a full proof, see the appendix at the bottom.

To see why this strategy is optimal, we first claim the following.

Claim 1.5 (P2's strategy when checked to): When checked to, P2’s optimal strategy is to check 100%.

Proof Sketch of 1.5:

If both players checked, they’d each win 50% of the time (each player has 50% equity). The average strength of hands in their ranges are the same. However, the key difference between P1 and P2’s ranges is that P1’s range contains hands that are both stronger and weaker than P2’s range. We say that P1’s range is polarized.

Polarization is relevant because the polarized player is game-theoretically incentivized to bet, while the condensed player is not. To see this, note that there are two incentives to betting: betting to get called by a worse hand or betting to fold outo a better hand.

Suppose P2, the condensed player, bets. Because both players know each others’ ranges, P1 will never call with QQ and will always call with AA. This simple counter strategy against P2’s bet ensures that P2 never gets called by a worse hand (QQ) and never gets a better hand to fold (AA). Because P2’s bet accomplishes nothing, P2 will always check if P1 checks to him. \(\blacksquare\)

Remark: In general, the player that is polarized has incentive to bet while the player that’s condensed has incentive to check (Key Concept 1). We now return to the main claim.

Proof Sketch of 1.4:

P1’s NE strategy

We’ll start by analyzing the incentives of P1’s hands. AA wants to get called by P2’s worse hands, KK. In contrast, QQ wants to make P2 fold his KK some fraction of the time. Thus, both hands (AA as value hands, QQ as bluffs) are incentivized to bet. So both hands should bet at least some time, but how often?

Suppose that P1 checks to P2. By Claim \(1.5\), P2 will always check back. Therefore, since AA is guaranteed the best hand, P1 should always bet 100% of her AA since the EV of betting (where P2 might call) dominates the EV of checking (where P2 always checks back).

The only unknown left to optimize is the fraction of QQ that P1 chooses to bet. We saw in Strategy \(1.3\) that if P1 bets 100% of her QQ, she attains an EV of 50 (half the pot). On the other hand, if P1 bets 0% of her QQ, then P2’s counter-strategy is to fold 100% of his hands, as he knows that P1 can only have AA. The EV of this strategy is also 50.

However, it turns out that if P1 bets exactly 50% of QQ, she attains an EV of 75 (details for why 50% are in the appendix). Here, P1 plays a mixed strategy–when she has QQ, she will choose either bet or check with some probability. Let’s try to understand why P1 should bet some, but not all of her QQ.

If a mixed strategy is a NE, then any action in the strategy (in its support) must have the same EV as the strategy itself. Thus, in order for P1 to maximize her EV, she needs to make P2 indifferent to calling or folding–the EV of either of P2’s actions needs to be made the same (Key Concept 2). To do so in this scenario, it happens that P1 should bet so that the ratio of value to bluff hands is 2:1. This betting strategy will yield an EV of 75, 25 more than the bet-all or bet-none strategies.

P2’s NE strategy

With P1 playing this strategy, P2’s EV for calling or folding are equal. This means P2 can play either with any probability, right?

Actually, no. Suppose P2 called 100% of the time. Then P1 can adjust her strategy to only bet with AA and check all QQ, yielding an EV of:

\[EV_1 = 0.5 (200) + 0.5 * 0 = 100 > 75\]The above is an example of P2 playing an exploitable strategy. Indeed, P2 fares well versus certain strategies (in this case, P1’s NE strategy), but fares much worse against P1’s best response (BR) strategy, where she bets only AA. Further, when P1 is playing a NE strategy and P2 is playing an exploitable strategy, P2’s EV can be no higher than if P2 played a NE strategy, as well. Any other deviation from NE can only increase P1’s EV (Key Concept 3). Similarly, if P2 folded 100% when facing a bet, P1 could just bet 100% of QQ, obtaining the entire pot (EV = 100). This, too, is highly exploitable.

There exists a mix of calling and folding that optimizes P2’s EV: calling 50% of the time and folding 50%. Any deviation from this NE strategy (e.g. calling 55%) will allow P1 to exploit P2 (e.g. by bluffing less with QQ and pure-value-betting). \(\blacksquare\)

Practical Implications of Key Concepts

We’ll start by elaborating on the key concepts highlighted. Then we’ll delve into their highly practical implications for your game.

Key Concept 3 (Exploitability and the Utility of Playing a NE)

If you play a NE strategy, the best your opponent can do against you (their BR) is to play a NE, themself. In a zero-sum setting, if both players play a NE, they both earn an EV of 0, and either player will only lose EV if they deviate from their NE strategy. This is what Game theory optimal (GTO) maximalists mean when they say that playing GTO cannot lose in expectation.

However, to evaluate the utility of playing a NE strategy in practice, let’s return to the assumptions we made. In a setting where you and I are playing a lot of hands together (10,000+), the following two assumptions become true.

- (Realizability) If my strategy has an edge on yours, I am able to realize that edge, by the law of large numbers.

- (Approximate Knowledge) Because we play so many hands, we can gauge approximately what the other person’s strategy is at each spot: how often are they betting, with what sizing, and with what hands?. This means that if you are playing a highly exploitable strategy, after 10,000 hands your oppoonent will catch on, adjust, and exploit your strategy.

Note that these two assumptions–that EV is all that matters and that we have perfect knowledge of the opponent’s (mixed) strategy– are assumptions we make in the game theoretic analysis above. Thus, in circumstances where we play a large number of hands against our opponent, it is important to play a sound game-theoretic strategy. In the 25,000 hand heads up challenge between Doug Polk and Daniel Negreanu, the reason Polk was over a 4:1 favorite was because he played a sounder GTO strategy.

However, in most poker settings these assumptions don’t apply. If you walk into a random cash game in a casino, the players at the table have no idea what your strategy is, so assumption 2 is invalid. They certainly aren’t playing perfectly themselves, so assumption 1 is also invalid. Thus, instead of playing a GTO strategy, it is often more profitable to play an exploitative strategy, where you gauge what your opponent’s exploitable tendencies are (e.g. betting 100% on the flop) and adjust your strategy to exploit it.

Still, learning GTO is crucial in being able to play stronger players and longer sessions. Having solid GTO fundementals can only help you as you play stronger players who have fewer exploitable tendencies and who also know how to exploit you back.

Key Concept 1 (Range Polarization and When to Bet)

When your range is polarized, your strongest hands are stronger than your opponent’s hands, and your weakest hands are weaker than your opponent’s hand. In our toy game, Player 1 had a perfectly polarized range while Player 2, conversely, had a condensed range.

We saw from claim 1.3 that it was highly suboptimal for Player 2 to bet into player 1. When Player 1 is polarized and facing a bet, she can always just fold her bad hands and call with her good hands. Against this simple BR counter-strategy, P2’s bet achieves nothing positive.

More generally, when you bet, you have two objectives: get called by worse hands or fold out better. If you can’t accomplish either, as when your opponent is polarized, you must check. This is why in single raised pots (SRPs), action is usually checked to the preflop aggressor. On most flops, the aggressor has more nutted hands in their range (Overpairs, top set, etc.), while the preflop caller has considerably fewer nutted hands, as they would have raised many of them preflop.

The general takeaway is that your optimal strategy is a heavily dependent on particular features of your range and your opponent’s range. In the special case where your range is perfectly polarized, betting is heavily incentivized as your nutted hands can stack your opponent’s worse hands, while your garbage hands can fold out better hands

Of course, in No-Limit Hold’em most spots aren’t perfectly polarized. Optimal play is extremely nuanced and complex. However, here’s two simplified heuristics that capture the most important features of ranges for deciding when to bet and how much:

-

Does my range have a nut advantage–are my best hands stronger than my opponent’s best hands?

-

Does my range have an equity advantage–on average, are my hands stronger than my opponent’s hands?

Using these two heuristics, let’s first address how frequently you should bet, if at all.

Regarding heuristic 1, we saw that in the toy game that a player at a severe nut disadvantage should check. But unlike the toy game, where polarization is very cut and dry, it is usually less clear in real poker who has a nut advantage, as both players may have nutted hands in range (sets, two pairs, etc.). My recommendation is that as long as you aren’t at a severe nut disadvantage, you are allowed bet, and otherwise you should check.

Assuming we can bet, we now need to decide betting frequency. Regarding heuristic 2, the larger your equity advantage, the more frequently you can bet. This is why in single raised pots, on a board like Ad Qh 3s where the preflop aggressor has a massive equity advantage, they are betting close to 100% of range (“range betting”), often for a small size.

Conversely, if you are at equity disadvantage, you should check more frequently, even if you have the nut advantage. For instance, suppose the preflop raiser bets all their hands on a flop of A-T-2, and the opponent calls. The turn card is a 3 (board is A-T-2-3). In this situation the flop bettor still has the nut advantage (having Aces, Tens, AT in range), but is actually at an equity disadvantage. This is because the flop caller’s range will be very dense in top pairs and second pairs (as they would have folded most of their worse hands to the flop bet), while the preflop bettor still has a ton of garbage in range (e.g. Queen high). Due to this range disadvantage, if the preflop bettor bets, they will usually bet at a low frequency (say, 40% of the time) for a large sizing. When they bet, they will only bet with their very strongest hands, along with some bluffs (and will choose a large sizing like 2/3 pot). This betting pattern is called “turn polarization”. With the remaining hands in their range (the weaker, middling hands), they just check.

Now let’s address how large you should bet.

In general, you should only bet large if you have the nut advantage. Intuitively, if you don’t have the nut advantage, you would like to keep the pot smaller as you are under constant threat of being stacked by your opponent’s best hands. If your opponent were to put in a lot of money with their best hands (and some bluffs), most of your hands would be in an incredibly uncomfortable spot. TLDR, the larger your nut advantage, the larger you are allowed to bet.

One more point: usually, you need to coordinate your betting frequency and your bet size. Unless you have a significant range and nut advantage, it is usually highly exploitable to bet large with a high frequency. As such, the “safest” and most common betting patterns are to bet small for a high frequency or to bet large with a lower frequency. Of course, this rule isn’t hard-and-fast. Here are more nuanced examples of common betting frequency and size combinations:

-

Large range advantage, large nut advantage (e.g. SRP preflop aggressor on Ad Qs 3h flop). Bet large (2/3 pot) and bet frequently (close to 100% of range).

-

Large range advantage, small to no nut advantage (e.g. SRP preflop aggressor on Qd Jd 10d). Bet small (1/3 pot) and bet frequently.

-

No range advantage or slight range disadvantage, but decent nut advantage (e.g. SRP preflop aggressor bets on Ad Qs 3h flop, the opponent calls, and the turn is a 2c). Bet infrequently, but bet large when you do.

-

Slight range advantage, little to no nut advantage. Check at a high frequency, especially when out of position. If you are going to bet, let it be in position and for a small size and low frequency. (e.g. SRP preflop aggressor on 6c 5c 4d).

Finally, let me address how position should affect your bet sizing and frequency. Being in position is an advantage for three reasons

-

You see what your opponent does before you act, giving you more information about their true range

-

If your opponent checks, you have the option to check back and see the next card for free (to “realize your equity” for free). In contrast, if you are OOP and you check, there is no guarantee that you get to see the next card for free, in the event your opponent bets.

-

If you bet from OOP and you get raised, you will be playing a large pot from OOP on future streets. This is usually an uncomfortable spot. Put another way, IP can apply a lot of pressure through raises.

Because of these points (especially points 2 and 3), you need to play more defensively when OOP. This means that you should generally decrease your betting frequency ( don’t bet with a lot of your marginal hands). Despite being OOP, you can still have many nutted hands in range. If you do, you might consider betting larger and less frequently than if you were in the same spot, but IP.

In addition to checking more marginal hands, you also need to check more nutted hands (“traps”) than if you were IP. This is because if you always bet all your strong hands, then when you check, your opponent will attack your weakened checking range. This would be less of a problem if you’re IP because when you check as IP, you immediately see the next card. But being OOP, you need to check some traps to protect the weak hands in your checking range against your opponent’s bets.

Key Concept 2 (Indifference and Bet Sizing)

Indifference is an important concept for constructing your strategies. In our toy game, player 1 made player 2 indifferent to his options of calling and folding by mixing in the correct number of bluffs in her betting range (“balancing her bluffs”). It was at the precise point where player 2 was indifferent that player 1 earned max EV. If player 1 overbluffed, calling became preferred. If player 1 underbluffed, folding became preferred.

When constructing your betting ranges in NLH, you should have a target set of hands in mind that you want to make indifferent or colloquially, to put in a tough spot. In theory, doing so denies maximal equity from these hands. In practice, doing so induces a ton of mistakes out of your opponent, as players make more mistakes when put in murky, 50-50 spots than in spots with an obvious correct play. When betting, have in mind the type of hand you want to target: top pairs/middle pairs, flushes, Ace highs, etc. This type should usually be a sizable portion of their range–don’t make an obscenely large bet, hoping to target the top 1% of their range.

A Framework for Poker Decisionmaking

When you have 5-10 seconds for each decision, it’s important to have a structured decision making process that takes into account the most important information of the hand.

Before you play, prepare the following offline:

-

Choose two bet sizes: one “small” bet size (e.g. 1/3 pot) and one “large” bet size (e.g. 2/3 pot). Your in-game decisionmaking will just be to decide whether you should check, bet small, or bet large. Note that on the river, you can also use the “all-in” sizing, which should be used only if you heavily polarize your betting range (i.e. you have a large nut advantage).

-

Memorize some preflop charts for single raised pots and 3-bet pots. This is like knowing your chess openings–you don’t want to have to deduce these in real time.

In the moment, ask yourself the following:

-

(Info Recap) Recap the important information. What actions you took, what actions they took, what cards came down, what position you are in (IP or OOP).

-

(Range Strategy) Roughly estimate your range and their range and ask yourself what your range wants to do in this spot. E.g. do I want to bet frequently and small, bet infrequently but large, etc.

-

(Hand Strategy) Assuming your range wants to bet, ask yourself whether your particular hand wants to bet. If you have a nutted hand or a strong draw, you want to bet to polarize. If you have a middling hand, you want check to get to showdown for cheap. If you expect your opponent to raise a lot of the time, consider whether your hand can withstand a raise. If not, you should consider checking that hand. In this way, you can determine your hand’s strategy in the context of your range’s strategy.

-

(Exploitative Considerations) Now consider any exploitative tells or tendencies you gleam from your opponent. If you think your reads are strong enough, consider deviating from the GTO baseline strategy (i.e. step 3) to exploit your opponent. There are a lot of good exploitative tells:

- Exploitable Strategies: If they always cbet flop with their good hands, but on this flop they check, then this signals extreme weakness

- Bet timing: When you have a nutted hand, you often have to think about whether betting or checking will be more profitable. Thus, if they bet quickly in a spot they should be thinking hard about, they’re probably bluffing

- Bet sizing: Do they use different sizings when value-betting versus bluffing? Some people size down when the value bet since they want to get called and size up when they want a fold. In another context, some people will bet full pot on the river when they have a strong hand they feel has not been adequately paid off; however, they would never airball bluff river with such a large sizing

- Intentional/Reverse Tells: This usually happens in big hands; if they are acting weak in a hand they’re heavily invested in, this signals strength. If they’re acting strong (aggressively placing down chips, staring you down), this signals weakness. Of course, the difficult part is judging whether they’re acting or being genuine.

- Table talk and interaction: A poker legend once said that if you smile at a player and they give you a genuine smile back, they’re likely not bluffing. I think this points to a larger observation that people are more relaxed when they actually have the goods, and you can try gauge this through how they talk and act in front of you.

- Early signs of disinterest: Usually if a player is on their phone at the beginning of a hand, they don’t have anything good

A Simple but Solid Strategy

Credit to Doug Polk for coming up with this strategy.

Categorize your hands into 4 categories:

- strong showdown hands (e.g. top pair)

- medium strength showdown hands (e.g. middle pair)

- strong draws (e.g. Nut flush draw)

- weak draws and garbage (e.g. gutshot straight-draw)

If you are not the preflop raiser, you should check to the preflop raiser, as they are polarized.

If you are the preflop raiser, then do the following.

- On the flop, if your opponent checks to you, bet your strong showdown hands and strongest draws, and check everything else.

- If you checked the flop, and your opponent checks the turn, then start betting your medium strength showdown hands and weak draws.

The rough intuition is as follows.

On the flop, you want to be polarized when you bet, betting your strongest hands and some bluffs. The choice of bluffs are your strongest draws because draws benefit from betting, to fold out hands with showdown value, like second pair. Moreover, we want to choose our strongest draws on the flop because we potentially need to bet 3 streets (e.g. with the nut flush draw, we’d want to barrel flop and turn), so we want to use the draws with the most chance of improving. The strongest draws are also capable of calling a raise, which you need to be prepared for if you bet the flop.

If we check flop and are checked to on the turn, then intuitively the opponent’s range is generally weaker than it would be had they bet. Against this weaker range, we can start betting our medium strength hands for value, and our weak draws as bluffs, again with the aim of polarizing.

Final Remarks

The strategy above is a nice starting strategy– better than “I flopped a pair, so I will bet” or “I will bluff beause I feel like it” strategies. However, it certainly is not optimal. E.g. if your only bluffs on the flop are strong draws (e.g. flush draws), then on turn cards that complete your flush, you suddenly have no bluffs. You just have to play the game more to figure out what other hands you should have in your betting ranges, and how your ranges change when your IP vs OOP, when it’s a 3bet pot versus a single raised pot, etc. But hopefully this article gave you a framework to reason about these things so that it’s easier to learn from your practice.

Appendix

Claim 1.4 (Nash Equilibrium for Poker River Game): P1’s nash equilibrium (NE) strategy is to bet 100% of her AA and 50% of her QQ, and check the other 50% of her QQ. P2’s NE strategy, when facing a bet, is to call 50% and fold 50%; and facing a check, P2 checks 100%. For this NE,

\(EV_1 = 75, EV_2 = 25\)

To prove this, we first show the following fact:

Claim 1.5 (P2's strategy when checked to): When checked to, P2’s optimal strategy is to check 100%.

Proof of 1.5: Represent P1’s checking range as \(\{AA : 1 - p, QQ : p\}\). Against this range, if P2 were to check 100%, he gets an EV of

\(EV_{2, x} = (1 - p) (0) + p (100) = 100p\).

On the other hand, the EV for betting is lower. If he bets an amount x, P1’s best response (BR) versus his bet is to fold 100% of her QQ and call 100% of her AA. The EV of betting is:

\(EV_{2, b} = (1 - p) (-x) + p (100) = 100p - x(1 - p) \leq EV_{2, x}\).

Thus, P2 will always check back when checked to, due to this polarization of P1’s range, where P1’s range contains hands both stronger and weaker than P2. Important Concept 1 Returning to the main claim,

Proof of 1.4: Suppose that P1 checks to P2. By Claim \(1.5\), P2 will always check back. Therefore, since AA is guaranteed the best hand, P1 will always bet 100% of her AA since the EV of betting (where P2 might call) dominates the EV of checking (where P2 always checks back).

Now, let q be the fraction of P1’s QQ that she bets. For now, let her bet size be 100. Consider 2 cases:

Case 1: q < 0.5. Then P1’s (unnormalized) betting range is \(\{AA : 0.5, QQ : 0.5q\}\). P2’s EV of folding is 0. But the EV of calling is

\(EV_{2, c} = 0.5 (-100) + 0.5q (200) < 0 = EV_{2, f}\).

Thus, when facing a bet (w.p. 0.5 + 0.5q), P2 always folds, with EV 0. And when facing a check (w.p. 0.5 (1 - q)), P2 is always facing QQ and will always win. His EV in this line is 100. The EV of P2’s strategy is then

\[EV_2 = (0.5 + 0.5q) * 0 + 0.5 (1 - q) * 100 = 50 (1 - q) \geq 25 (*)\]Case 2: q > 0.5. Then P1’s (unnormalized) betting range is \(\{AA : 0.5, QQ : 0.5q\}\). Facing this range, the scenario is similar to example 1.3 and P2’s BR is to call 100% when facing a bet, and to check 100% when facing a check. It can be verified that P2’s strategy’s EV is

\[EV_2 = 150q - 50 \geq 25 (* *)\]Examining equations \((*)\) and \((* *)\), P1 can minimize P2’s EV (hence maximizing her own EV) by setting q = 0.5. Thus, her strategy is to bet 100% of AA, bet 50% of QQ, and check the other 50%.

By “balancing” her betting range in this way, P1 makes the EV of P2’s call and fold actions equal, making P2 indifferent to these actions. Important Concept 2 Moreover, she guarantees that P2’s EV is at most 25, i.e. that her own EV is at least 75.

With P1 playing this strategy, P2’s EV for calling or folding are equal. This means P2 can play either with any probability, right?

No. Suppose P2 called 100% of the time. Then P1 can adjust her strategy to only bet with AA and check all QQ, yielding an EV of:

\[EV_1 = 0.5 (200) + 0.5 * 0 = 100 > 75\]The above is an example of P2 playing an exploitable strategy. Even though against P1’s NE strategy, he nets the same EV as his actual NE strategy (which is some mix of calling and folding), his strategy fares much worse in EV against a BR strategy: P1 betting only AA. A further remark is that when P1 is playing a NE strategy and P2 is playing an exploitable strategy, P2’s EV can be no higher than P2’s EV using her NE strategy. That is, when P1 plays a NE strategy, the worst P1 can do is when P2 also plays a NE strategy. Any other strategy P2 plays can only be beneficial for P1’s EV Important Concept 3.

Similarly, if P2 folded 100%, P1 would just bet 100% of QQ, netting the entire pot (EV = 100), while P2 nets an EV of 0.

There exists a mix of calling and folding that optimizes P2’s EV: calling 50% of the time and folding 50%. Any deviation from this NE strategy (e.g. calling 55%) will allow P1 to exploit P2 (e.g. by bluffing less with QQ and pure-value-betting).

Thus, at equilibrium, P1 bets 100% of AA and 50% of QQ, and checks 50% of QQ. P2 calls 50% and folds 50%. \(EV_1 = 75\) and \(EV_2 = 25\).